In This Article

We’ve made some slight changes to our quarterly format. We understand that some of the more recent quarterlies have been a little long. When I left the institutional side of the business, my goal was to provide investors with what I would want to hear if the roles were reversed.

These reports are far from just numbers, there is an education of some degree in each quarterly, many reports will be shorter, though at times others will be a little longer. Either way, there is likely perspective or insight you most likely have not heard or considered before.

I’ve attempted to focus the first section of this piece on current market conditions, the model and our discipline. We also discuss our forward-looking direction and what shifts we anticipate making given what we are currently seeing. The first section is easy reading – 10 pages with a handful of charts – yet solid and extremely informative.

The information contained in the balance of the note discuss and explore some of the more head scratching, mind numbing moments of the quarter (in my opinion). We address the “do as I say, not as I do” mind set and cognitive dissonance that exists among some of the most high profile CEOs on Wall Street. We tackle and vehemently disagree with Jamie Dimon stating those who “question buybacks and dividends are ignorant as to how capital markets function”, more importantly, we explain why. We dive into the fall of GE and detail how our capital preservation discipline saved us while many other GE owners are down over 60% in 8 months. We question why Bernanke’s Wile E. Coyote moment was the least important part of Bernanke’s interview with AEI and what really goes on inside the Federal Reserve based upon the personal experience of Danielle DiMartino Booth, former top advisor to former Dallas Fed Bank President, Richard Fisher.

There is a ton of great information in here, whether you agree with some, all or none of my thoughts, hopefully, at the very least, we made you think as to how you can protect your investments a little better than you currently might be?

I welcome respectful dialogue and feedback. As I do my best to cite my information, I’d kindly ask you do the same. As a new firm, we are adjusting on the fly and will continue to do so until we have things dialed in for the majority.

Let’s get into the numbers, make our observations and then talk outlook:

2018 YTD for the S&P

2.65% Total Return

2018 YTD for the DJIA

(-0.73) Total Return

2018 YTD for our Equity Solutions Model

(-0.81%) **Total Return

Observations:

For those who merely look at performance numbers as of a specified date (i.e. quarter end) vs. the S&P and DOW, our numbers this quarter may seem a bit, “Meh”. We continue to slightly lag the S&P, while our performance was “in-line” with the DJIA (Dow Jones Industrial Average).

There was a tremendous amount of volatility throughout the quarter, which triggered a handful of our capital preservation strategies. At one point, our cash position rose to 28.5% before we deployed a bit more capital leveling it off in the 15.5% range. Our capital preservation strategy put the breaks on our 3 week slide, reduced our risk and continues to afford us the ability to be opportunistic as attractive situations present themselves. Again, we enter Q3 with a strong cash position.

In the past, I’ve described benchmarking as of a specific date in previous notes, as “a snapshot in time” Without question, if your “need” was immediate cash the two weeks of the quarter, our returns would have left you short of the two “classic” benchmarks, better than many but not our best. Though, there is a reason we persistently urge you to dig deeper into the numbers. For better or worse, it’s tremendously important you understand what you own and why.

Let’s stretch out that “snapshot in time” for a moment and look at the entire quarter.

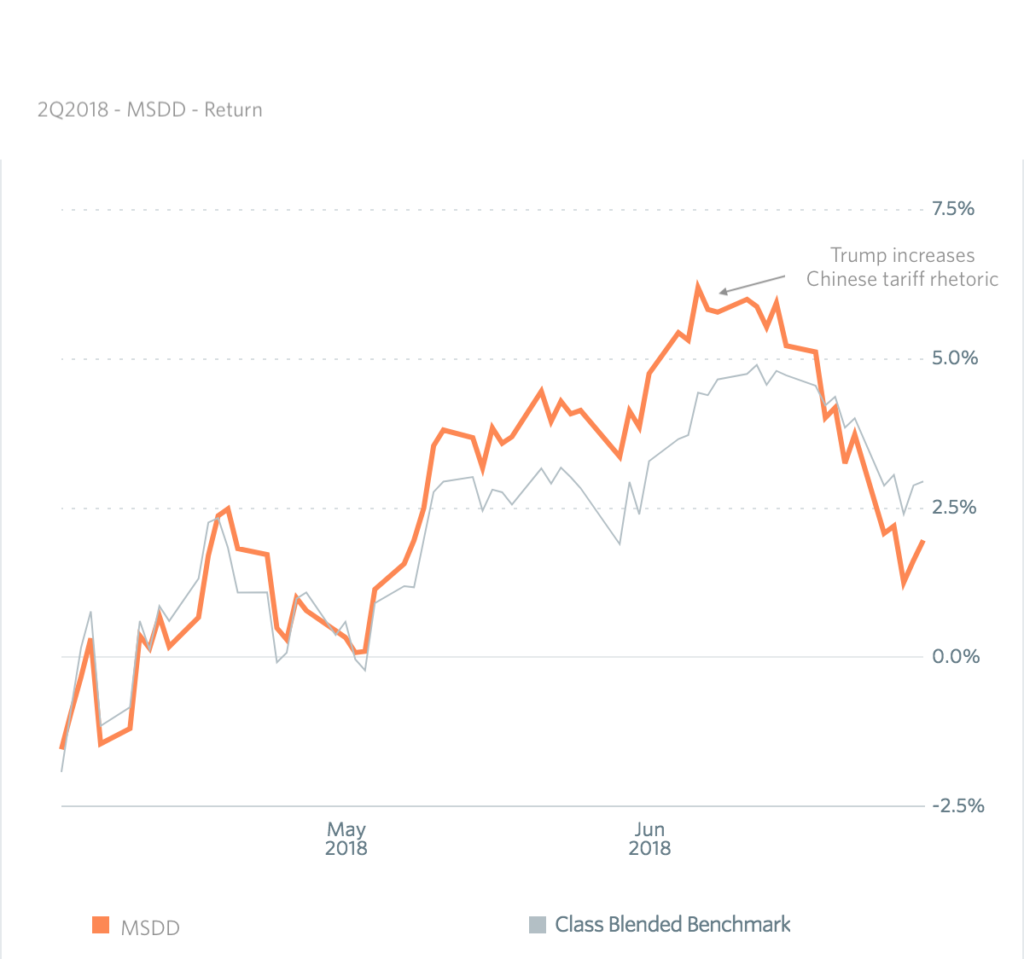

The below chart is our quarterly performance vs. Class Blended Benchmark (S&P 500/90-day Treasury bill based on % of cash on hand). The orange line represents our MSDD model (Managed Solutions Disciplined & Diversified). Our discipline in “protecting downside” our diversified in being “more global” with what we own; Investing in what we believe will provide Alpha while not being solely correlated to one specific sector or index.

As you can see, for much of the quarter, we produced solid outperformance; we were well ahead of blended benchmarks and right on the S&P while taking on less risk and holding significantly more cash. The model was doing what it was supposed to be doing.

So what gives? What led to the underperformance over the last 3 weeks?

In a single word “Tariffs”

While we’ve been talking and writing about tariffs from the beginning of the year, rhetoric exploded in early June adversely affecting many of the Chinese local A-share names we have been holding as well as some bell weather DOW and listed Chinese tech names we own(ed).

Clearly, China has been the primary “tariff” target of President Trump, in turn, Chinese companies as well as many global U.S companies which see a great deal of their revenue generated from outside the US (i.e. Boeing, Caterpillar, Bidu, Alibaba, Tencent and Naspers to name a few), have seen a sharp decline in their stock prices. Many of these names generate over 50% of their revenue from outside the United States.

Given the increased rhetoric, a great deal of them have moved into what would be classified as “bear market” territory in a mere 3-week time frame (which happened to coincide with quarters end). Still the model finished the quarter doing as it is designed to do. (Cutting losers before they become problematic)

It’s no secret Chinese A-share names have been a primary thesis of ours for years. The performance (in many of these names among others), over the years has produce returns well in excess of traditional benchmarks allowing us to hold larger amounts of cash and pull back on risk, while maintaining YTD total performance numbers exceeding or in-line with these traditional indices we now slightly trail.

We acknowledge the recent fall from grace the last three weeks is visually noticeable, yet, so is the outperformance over the majority of the quarter. Moments of underperformance will exist from time to time. Our belief is this will prove to be a knee jerk over-reaction as the reality of forced money flow into many of these names outweighs rhetoric and becomes more prominent as MSCI percentages grow, though, until proven otherwise, we remain committed to our disciplines and have sold those names our disciplines have directed us to.

Having said that; lets take a deeper dive into our thesis and how we’re positioning ourselves given the current market conditions.

China!

Let’s stick with the China theme while fresh in our minds…

We know the names we own well, we understand why we own them, yet we will reiterate that we are not “married” to any specific names, discipline rules our model. Having said this, we’ve come out of some Chinese local A-share holdings as well as our U.S. position in Caterpillar (CAT), which have triggered their respective capital preservation strategies. In the short term, we’ll look to play good defense, keeping powder dry.

As tariff talk calms, do NOT be surprised if we find ourselves back in similar or even some the same names, as there are some irrefutable truths that we believe warrant such ownership, yet, not at the expense of breaking our own rules.

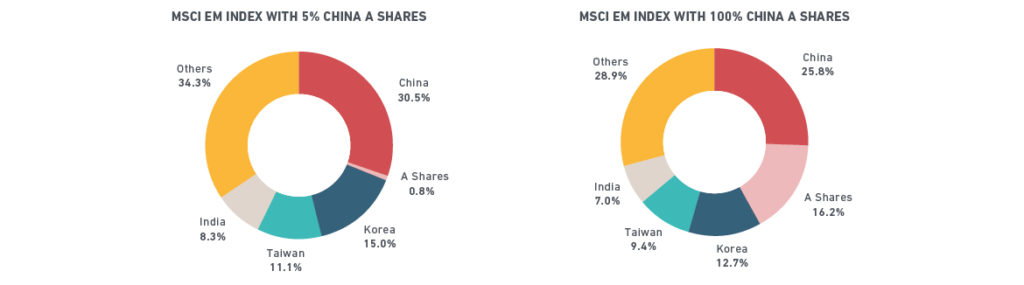

- The MSCI story we’ve written at length about. May 31, 2018 was the first time in history the MSCI indices have owned Chinese A-shares. What occurred on May 31, 2018 amounts to a rounding error in relation to what the final holdings of the MSCI indices will be and the role Chinese A-shares will play. See below as well as click here for current and future projections directly from MSCI:

As of market close, May 31st, the inclusion of a mere 5% of Chinese A-shares currently accounts for 0.8% of the final number that these names will eventually represent. Within 3-5 years, they will account for nearly16-17% of the MSCI Emerging Markets Index.

While the Chinese A-shares will first be introduced to the MSCI “Emerging Markets index”, suggesting China is “Emerging” today is a stretch. When we speak of China today, we’re talking about the second largest economy in the world with many major Chinese cities significantly more technically advanced then many US cities, far surpassing the US in digital payments already. Shanghai has a population larger than the top 10 US cities combined. There is an estimated 94% of our roughly $13 Trillion dollar pension fund market following the MSCI indices. While Chinese A-shares are a “lock” in the MSCI EM index, it is likely be included in other MSCI indices over the next 5 years. (More on the local Chinese A-share inclusion from Bloomberg here)

- The Chinese have a problem, one more serious than here in the United States. An aging Chinese population coupled with a multi decade, one-child per family policy has created drastic pension fund shortfalls. In late 2015, the Chinese government ok’d pension funds to invest up to 40% of their assets in the Chinese A-share markets. This is being done through the NCSSF (National Council for Social Security Fund) as well as through pension and mutual fund managers, insurance companies and securities firms. Currently invested assets by pension funds are small, however, should 30% of Chinese pension assets be invested into their equity markets, rough estimates suggest, an additional $1 trillion in Yuan would flow into Chinese local A-shares.

Items #1 & 2 will shift Trillions of dollars into these Chinese equity markets, tariffs or not. When you combine items 1&2 with #3, the environment has never been more attractive to be invested in these names.

- The below chart shows us how inexpensive Chinese equity markets currently are vs. the S&P on both, a Price to Earnings (P/E) and Price to book value basis (P/BV). Chinese stocks haven’t been this cheap vs. the S&P 500 in decades (Per Bloomberg:

Having stated the above:

We believe in defining clear, realistic investment goals, and remaining disciplined to them. We focus on controlling what we can; while all too often, the industry focuses on metrics, which cannot be controlled based upon too many variables.

So what can we control with relative certainty?

Said simply, our downside.

We have a very clear understanding of where we will be selling a name the very day we buy it (to the downside). We describe this as “cutting our losers before they become problematic”. That doesn’t mean we’re willing to lose money on every trade, for once our capital preservation strategy on any given name moves above the price we paid for that respective company, it would take a very rare event, which would produce a loss from that holding based upon our disciplines. Our strategy also allows our winners to run (move higher) than most price targets.

Our strategy has a stark contrast to the vast majority of money managers that do the exact opposite, focusing on upside price target. There are numerous issues with this thought process (too long for a quarterly) but the obvious being, nothing says a specified companies stock price will ever reach the analysts desired price. Even when speaking of the best analysts in the industry, their numbers and price targets are hypothetical guesses based off countless variables.

These many assumptions, which drive countless variables, are driven by earnings releases as well as management conference calls (which closely follow the earnings release). Analysts will often make adjustments to their models and ratings based upon management’s “tone” and forward looking guidance on these conference calls. You read that correctly, tone and managements word for it…

In many cases, traditional earnings releases typically do not use GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principals) when reporting their earnings. Additionally, what earnings releases include now, more frequently than ever is adjusted earnings, which often strips out charges and assumptions (a form of financial engineering done by management). Some firms have gone so far as to use, “community-adjusted” earnings, which ultimately worked out to be earnings adjusted and adjusted (multiple times) before management actually felt comfortable enough with them before releasing them (they don’t teach this stuff in finance 201p). It should be noted that by rule, auditors would NOT audit non-GAAP numbers.

So to sum it up, the vast majority of investors focus on earnings releases, which can send a stock price soaring or plunging based upon an earnings release which uses financially engineered numbers put together by management that have NOT been audited as these releases often do not use GAAP accounting metrics.

And virtually no analysts adjust their numbers based off the companies official releases (10-k’s and 10-q’s) which ARE audited and DO follow GAAP accounting practices, but are often released so close to the following quarter’s next scheduled earnings release, you’re virtually into a new earnings season by the time they become available. It’s also worth noting these documents can be hundreds of pages making it “difficult” for analysts to read thoroughly when they cover so many companies within a specific industry.

Still, most portfolio, asset and hedge fund managers continue to base their sell strategies off of their forward-looking earnings and revenue growth models outlined above.

We mitigate downside.

Clearly, forward-looking models are an important tool, but what happens when everyone is wrong? What happens when management teams who want their stock prices to move higher are a bit more ambitious then reality? What happens when the consensus view of “forward” is completely off the mark? Not just with one particular name, but markets as a whole?

Think 2007-2009; the market slashed prices well before any analysts got a chance to adjust their earnings models and revenue forecasts; stock repurchase plans ceased immediately, dividends were slashed again and again.

To reiterate, we differentiate ourselves from the vast majority of Wall Street managers by understanding where we will sell a name the very day we buy it. This is something we can control with a much greater certainty (within reason). Regardless of name or how much we like a particular story, our goal is to live to protect our capital and mitigate risk.

Why is all of this important?

FAANG +M

People see “markets” moving higher and compare their performance vs. a standardized benchmark as a measure of performance. What most people today aren’t paying attention to are how very lopsided markets are at this moment in time.

Recent CNBC data suggests 3 stocks are responsible for 71% of S&P 500 returns and 78% of the Nasdaq100 gains.

Amazon, Netflix and Microsoft

If you add 3 more names, Apple, Google (Alphabet) and Facebook the aggregated 6 names account for 98% and 105% of the aforementioned indices returns respectively. Many people don’t understand that the FAANG +M trade on the Nasdaq, but also comprise much of the S&P 500 based upon their size and weight.

The FAANG trade has been the most “crowded” trade on Wall Street for the past 6 months. Additionally, investment firms are now creating synthetic bond instruments tied directly to these names. As reported by Bloomberg: A hidden FANG trade is rising thanks to these exotic bonds. While I can’t tell you how long the outperformance from these 6 names will last, I will say, overcrowded trades often don’t end well.

Patience, at times… is prudent.

Some of you have noted the recent activity near quarters end. While much of this was a “rebalance”, it is important to note that we have added a few names to the model, slightly shifting the complexion of our portfolio to reflect recent market actions which mirror late stage bull market characteristics. We may be a little “early” with these trades; but these holdings have the ability to provide significant Alpha should things unfold as we believe they will. Though, as always, scripts don’t always play out exactly as written, so we will mind our capital preservation strategies on the entire portfolio, these new additions being no exception.

Again, as mentioned, we understand where we are relative to popular benchmarks, though; in keeping our finger on the pulse of the overall markets, becoming a 6 name tech fund to chase yield (and ridiculous valuation) wouldn’t be prudent at this time.

Technology names have begun to separate from the rest of the pack, Biotech is following in suit, while traditional staples like Disney, General Mills and Hershey’s are now significantly lagging. Signals of a late stage bull market rally… The chart below illustrates the recent separation.

Timing is very difficult to accurately predict, yet we’ve got our road map and we’re following it, though, sometimes it’s worth pulling off the highway in the middle of a “white out” snow storm then it is to press your luck and get rolled by a jack knifed tractor trailer. I’m confident in our future.

While we are not looking to be “active traders”, given the volatility typical of late stage bull markets, we feel there is no such thing as being too cautious. Our efforts look to mitigate significant downdrafts should, a. equity markets fall from grace or b. bond yields spike (adversely affecting bond holders), two very likely scenarios (the “when” being the million dollar question). Again, this is why we sold certain names putting the brakes on our 3-week slide. (Scenarios A&B can occur simultaneously). We are very likely to revisit these names in the future.

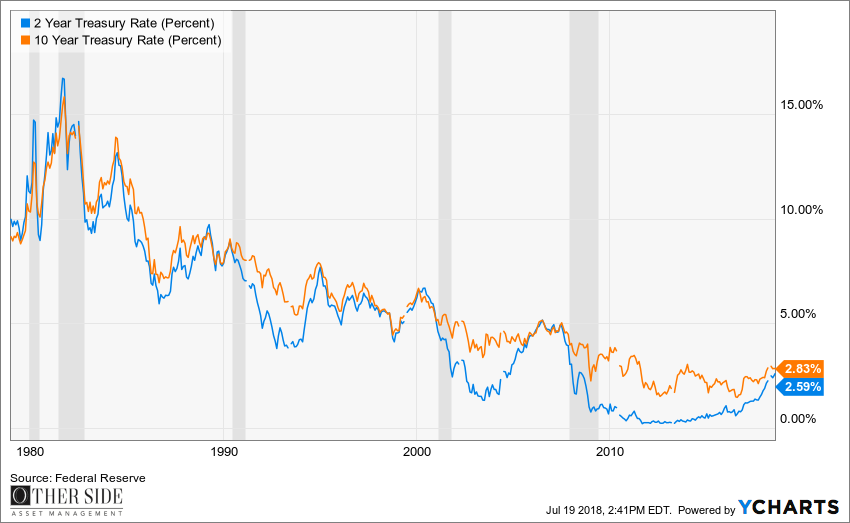

We’ve talked at length regarding the correlation between the 2-year-treasury rate (blue line below) vs. the 10-year-treasury rate (orange line below). Vertical grey highlighted area denotes recession. You will note that each recession dating back into the 1970’s was preceded with an inverted yield curve (Blue line crossing over the Orange)

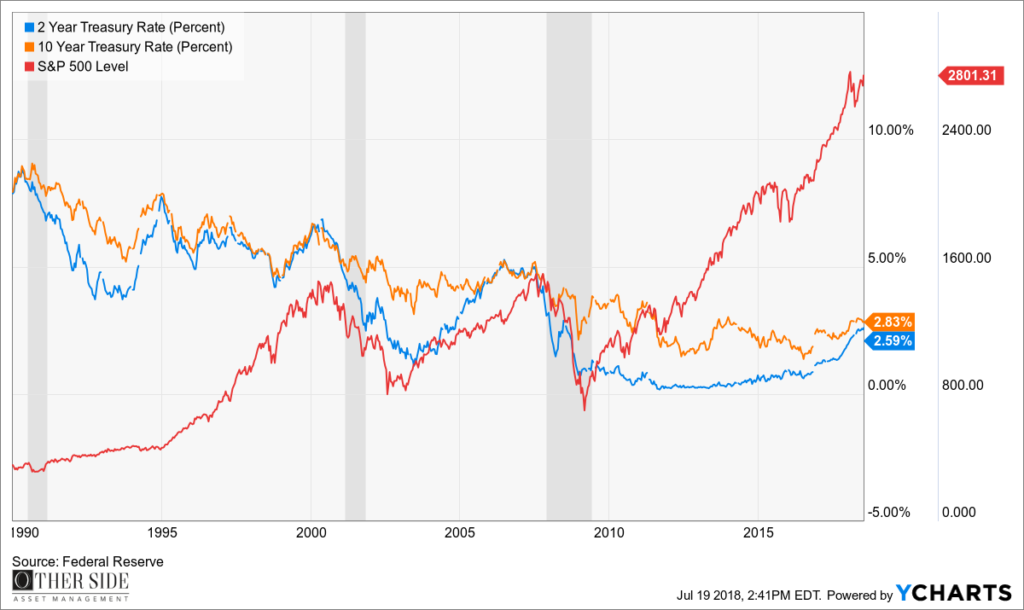

In the chart below, we’ve overlaid the S&P 500 on top of the 2-year/10-year relationship.

You will note that each time the 2-year-treasury note inverted the 10-year-treasury note; the corresponding reaction to the S&P 500 (Red line) was a significant sell off leading us into an economic recession (Grey vertical highlights). Currently to date, no lines have crossed, nothing has inverted and this is only one health indicator we are watching. We will maintain our disciplines, and continue to remain cautiously optimistic.

We’ve frequently discussed the prevalence and recurring “volatility” theme a late stage bull market would likely bring. We suggested this well before the volatility came; regardless, it’s here. With no one knowing when the WHEN is finally visible and obvious to all – our capital preservation strategies should be a welcomed life preserver while most investors are aimlessly floating at sea.

Stay long, stay cautious, and follow your disciplines…

“Ignorant of how capital markets function”

According to research firm TrimTabs, as reported by CNN; U.S public companies bought back a blistering $436.6 billion (with a B) worth of stock in the 2nd quarter of 2018. This nearly doubled an already record setting Q1 ($242.1 billion), at this pace; buybacks should crush the consensus yearly estimate of $800 billion by midway through Q3. These are truly astronomical numbers.

These buybacks continue to be a tailwind for equities for the remainder of the year (at worst case, significant support); not to mention a windfall for investment banks that handle corporate share repurchases.

Following a June 5th call with reporters, acting in his role as chairman of the Business Roundtable, JP Morgan Chase CEO, Jamie Dimon reportedly had some relatively strong words for those who question “buybacks and dividends”. As reported by the Washington Examiner following the call:

“I think it’s a tremendous error for people to think there’s something wrong with stock buybacks and dividends,” Dimon said. “That is a natural function of capital markets and the proper deployment of capital.”

He continued:

Companies return money to investors, he explained, when they don’t have a good use for it. Then, investors are able to put the money to a “higher and better use.”

“For the life of me, I don’t understand how anyone can say that’s a bad thing,” he remarked. “That is coming from people who are basically ignorant of how capital markets function.”

Then call me ignorant… I’ve been labeled worse.

Once upon a time, corporate buybacks were a large part of my daily responsibilities. I was to call C-level executives at small and mid cap financial institutions in an effort to wiggle our way into a companies buyback program, often looking to lock companies up in what’s called a 10b-5 plan. This is a plan that allows companies to repurchase shares while in a quiet period. A quiet period is a period of time companies can’t speak with outsiders or be active in markets; the time period typically precedes the release of financial information to the public. This quiet period is designed to “prevent” any one investor from having information prior to all others have access to the same information.

Our group was fairly successful at doing so. My senior partner at the time had (has) tremendous relationships with many investors who held larger blocks of stock in many of the financial institutions we were very active in.

I worked the institutional side of the business for nearly a decade, while I’m sure the hate mail will flow after suggesting this, the 10-years I spent on the retail side of the business previous to my stint on the institutional side provided me with what I would equate to be a high-school education at best, and I was what the industry would consider to be a successful broker with over $100 million under management, generating significant commissions.

I left the institutional side with an understanding of the business more valuable than anything taught in our US education system. It wasn’t just being on the institutional side of the business that made the difference. I honestly believe it was having a bird’s eye view of how different facets of the industry worked, while at the same time, reading completely independent research in that of Stansberry Research.

Reading internal research and working order flow from “smart money” to buy names like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac while the smaller, independent Stansberry research was suggesting these were bankrupt companies (with their reasoning being much more clear and concise, less contrived) at first was confusing. Stansberry predicted the decline and bankruptcies or many companies many months in advance, while most major firms (including ours) maintained buy or hold recommendations in the face of major declines. It took time to understand the “whys,” but once I connected the dots, it became very clear to me that I could no longer continue with what I was doing. At the time, I didn’t have the platform to vehemently disagree with those “paying the bills”.

It wasn’t easy making the decision to leave an extremely good living/paycheck to start over again, but it was the right thing to do. My vision of how I could help people was quite different (even contradictory) from those immediately above me. I left on my own accord; there was no “good” time, but it was definitely the “right” time.

Life with my old boss was by no means easy; though, in the world of financials, thrift conversions, and Mutual Holding Companies (MHC’s), he’s a savant; I was lucky to have had as much time with him as I did.

Anyone of significance that plays in the MHC, thrift space either should speak with Guy Malaby or already does. While I am not at liberty to provide a client list, I will say many are considered to be some of the most brilliant minds on Wall Street. These are big named thinkers, yet Guy’s mind is typically 5 steps ahead of most.

As mentioned above, one of my roles was to find banks willing to repurchase their own stock. With these firm bids in hand (or working orders); we could search for natural sellers (if we didn’t already have one). A natural seller is an institution holding sizable amounts of stock looking to sell larger amounts of stock (or blocks) in a thinly traded name at one time rather than working orders in the markets. Say, a bank wants to buy 100k shares – an institution (or group of institutions) wants to sell 100k shares, that stock can exchange hands in a single “cross” transaction (pending certain trading rules are followed), never directly affecting the price of the stock.

However, there are many inherent conflicts of interest with this type of business. First, the obvious; representing a seller whose goal is to get as high a price as they possibly can for what they are selling, while also representing a buyer who clearly should want to buy the stock for as cheap a price as they possibly can.

Here’s the thing… Most companies repurchase their own shares back at the absolute wrong time. It was typically much easier to find companies willing to repurchase their shares when valuations were high and stock prices were inflated. (Good for us, as it’s how we got paid, but not always for the company or it’s shareholders).

Just as investors attempt to find “value” when purchasing shares of any company, so too, should a company when making a decision to buy back it’s own shares. Repurchasing shares while trading at 250% of tangible book value or 20 times earnings may not be the smartest way to deploy that capital?!

Tangible book value (also knows as net tangible assets or net tangible shareholder equity) is the “total net asset value” of a company (book value) minus intangible assets (patents, goodwill, intellectual property, etc).

Tangible Book Value per share = Net Tangible Assets/ Total Shares outstanding

When buying shares back below Tangible Book Value (TBV) a company is reducing the number of shares outstanding faster then their equity; this is typically accretive to earnings, but more importantly, to tangible book value as well (i.e. it increases the value of the company). Said differently, when the denominator of the above equation decreases faster than the numerator, the end result is a larger number. A larger tangible book value means the company should be worth more.

This, my friends, is a good deployment of capital…

For years Warren Buffett had been critical of share repurchases; the below if from his 2012 letter to Berkshire shareholders:

“Charlie and I favor repurchases when two conditions are met: first, a company has ample funds to take care of the operational and liquidity needs of its business; second, its stock is selling at a material discount to the company’s intrinsic business value, conservatively calculated.

We have witnessed many bouts of repurchasing that failed our second test. Sometimes, of course, infractions – even serious ones – are innocent; many CEOs never stop believing their stock is cheap. In other instances, a less benign conclusion seems warranted. It doesn’t suffice to say that repurchases are being made to offset the dilution from stock issuances or simply because a company has excess cash. Continuing shareholders are hurt unless shares are purchased below intrinsic value. The first law of capital allocation – whether the money is slated for acquisitions or share repurchases – is that what is smart at one price is dumb at another. (One CEO who always stresses the price/value factor in repurchase decisions is Jamie Dimon at J.P. Morgan; I recommend that you read his annual letter.)”

Did you catch it? You read it right… June 5th Jamie Dimon called those who question buybacks and dividend “ignorant as to how capital markets function” yet his annual letters preach price sensitivity to the point Warrant Buffett suggests investors read Dimon’s annual letter. (MUCH more on this later)

The problem or challenge is, most investors (of all kinds) retail, institutional and corporate, run away from buying equities when things are cheap, yet they get tied up in the euphoria of buying equities when equities are historically overvalued (including corporate repurchases).

There are responsible ways to treat the capital of a company and just because you have the money, doesn’t mean that a buyback is the best use for that capital. This is a vicious cycle, which hasn’t been broken in my 22 years in this industry, and I doubt it ever will.

Jamie Dimon is a man who heads one of the most powerful and influential investment banks in the world, he is by no means ignorant as to how capital markets function, though what he and most other C-level executive in the industry, literally banks on, is that the majority of investors and financial media remains ignorant as to how financial markets function. I wish I had been on the call to hear it for myself. I prefer not having to rely on outside reporting as it can often be misconstrued; yet everywhere I read quotes Dimon the same way.

Casting a large dark cloud over those who “question” these uses of capital sets a dangerous precedence, either you’re with me and on board with dividends and buybacks or you’re “IGNORANT”, now choose. Killing the independent, minority voice is a very dangerous, slippery slope.

Without question, AT TIMES, in certain environments, at the right prices, buybacks are a good (even great) use of capital. However, it is irresponsible, misleading and flat out wrong to suggest buybacks are always a good use of capital.

Currently, many insiders don’t care if their companies are “overpaying” for shares. A recent study reported on by the Wall Street Journal which you can read here, shows insiders have been using these recent buybacks as their own exit strategy; selling nearly 5 times the amount of stock into a repurchase plan vs. outside of one. No wonder C-level executives don’t care if they are overpaying, wouldn’t you want to “cash-out” of your shares at highly overvalued prices, too?

Jamie Dimon will never fully educate you on how capital markets work, though, you should make every effort to understand why executives don’t want people asking too many questions; buybacks and dividends included. I’ll attempt to illustrate why with what was one of the most prominent names on Wall Street for decades, until recently…

The Fall of General Electric

As of June 26, 2018, General Electric (GE) has been removed from the DJIA (Dow Jones Industrial Average). In the early 2000’s, General Electric (GE) was one of the largest blue chip companies in the world. While caught in the troubles of the great recession, receiving government debt guarantees for nearly 4 years (incurring no cost) the last 8 months have been publically difficult with its share price dropping from over $33 into the mid $12’s, a 60% plus decline. Adding insult to injury, those who own the name likely hold an over sized position given the name historical ties being synonymous with safety.

Over the last decade, GE has returned nearly $50 billion in capital to shareholders in the form of buybacks and dividends.

Did they strengthen their balance sheet? NO

Did they buy or invest in better businesses? NO

What they did was weaken their balance sheet by borrowing the money to support these strategies (breaking Buffett’s buyback rule #1). Former CEO, Jeffrey Immelt and his board of directors, bankers and advisors left this once strong behemoth with over $60 billion in debt; barely able to generate enough free cash flow to make its interest payments on this cumulative debt…

Again, they borrowed money, to buyback stock and pay dividends; all to manipul… (Cough, cough) I mean, reduce their share count to meet Wall Street earnings estimates, while saddling the company with copious amounts of debt (more on this in a second) through financial engineering.

Here’s the kick in the teeth… $30 billion of that $50 billion “returned to shareholders” in the form of dividends and buybacks came between 2016 & 2017, which just happened to be the year before and of, then CEO Jeffrey Immelt’s retirement. ($24 billion was buybacks)

In an amazing turn of events (insert sarcasm), GE found it’s way into the low $30’s. Immelt’s departing options, which were virtually worthless the previous year, closed to the tune of over $90 million dollars, net positive; in total, he likely left GE with a retirement close to $211million, per Fortune.

Each and every time GE raised capital or borrowed money, it was done with the help of Wall Street investment bankers. When GE rolled hundred’s of billions of dollars in the short-term paper markets leading up to the crash of 2007-2009 an investment banker made obscene amounts of money. When GE was leveraging their AAA rating to gain access to this money, and then use it to buy sub-prime credit card receivables or $3-billion dollars worth of Polish Adjustable Rate Mortgages, did the ratings agencies (who get paid to provide unbiased ratings even though they receive compensation for the rating) track or think about what they were doing with this newly acquired debt?

How many analysts stopped for a second to think, does this make good business sense?“ How many analysts even knew they bought Polish Adjustable Rate Mortgages – shamefully, I did not. What investment bank sold them all of these sub-prime assets that they bought? Some investment bank/banker sold it to them? WHO?

A triple-A rated company borrows hundreds of billions of dollars, buys subprime assets with it, which then accounted for over 85% of their revenues and no one said boo?

We will likely never know the exact answers to all the above questions, but to me the “WHY NOT” is simple… I’ve lived it; I’ve watched it first hand… Not specifically with GE, the name is insignificant; the bottom line is all about money and the big money is made in the relationship.

“No CEO is showering money on Wall Street like Jeffrey Immelt. And no Wall Street CEO is catching more of it than Jamie Dimon.”

More from the Bloomberg report:

Over the past five years, Immelt’s GE has paid Dimon’s JPMorgan $167 million in merger and acquisition fees, as GE jettisoned lending units to revive the parent company following the financial crisis.

Cont…

GE has been a good friend to all of Wall Street, of course. Over the past five years, it’s spent $1.6 billion on fees for deals, bond sales and capital-markets advice, according to Freeman.

At the end of the day, the investment banks will squeeze every last dime of revenue from a client. In good times as well as bad, who gets the merger deal, capital raise (bond, equity or preferred), sale or divestiture, IPO? Who gets the buyback business? Who’s exercising management’s cashless options? These are all “cash cow” revenue sources for these investment-banking firms, even when they sell a deeply troubled company that has fallen out of favor; and it all boils down to the relationship.

Being in control of the above gives you access to the deepest of pockets; the multi-billion dollar mutual fund buyers, pension and hedge funds, private money managers who want these deals.

It’s all “relationship driven”, but one things is for sure… The relationship that matters most is the corporate relationship, not the little retail guy (regardless of what all the commercials say). Fee based retail for most firms is nothing more than a fairly predictable base revenue stream.

JPMorgan has enjoyed a long storied, 125-year investment banking relationship with GE.

Does Mr. Dimon really think borrowing money to return $30 out of the $50 billion spent over a decade, in a single year makes sense? Does he believe saddling GE with nearly $60 billion in long-term net debt is a good use of capital? Or might his firm be interested in capturing its fair share of the fees GE has paid out in the name of capital raises, debt offerings, advising on divesting holdings and/or executing share repurchases?

Is there even the slightest of chances that JPMorgan’s investment bankers had eyed up GE like a lion king circling his prey, as the $1.6 billion dollars GE spent over the last 5 years on deals, bond sales and capital-markets advice would certainly be split amongst other firms, but the lion share should go to the industry leading bankers, leaving scraps behind for the hyenas, jackals and turkey vultures? Is there any chance the enormous bonus pool could have clouded the judgment of corporate finance bankers?

Monday, January 22, 2018, Bank of America Merrill Lynch downgraded GE! Hold up… one sec… sorry, just reading a little further here – Ah, yes, that makes sense. After GE’s stock has dropped roughly 50% in a 6-month time frame, the downgrade was from “Buy” to “Neutral” – I’m sure that brought clarity to those investors who continued to hold the name based upon their previous “Buy” recommendation.

Our outlook “reflects lower earnings estimates, zero equity value assigned to GE Capital, and lower value assigned to GE Digital initiatives, as we don’t see the market paying up for this optionality,” the Bank of America note says.

The analyst continued:

“The relative size of the charge vs. expectations and limited disclosure related to potential off-balance sheet liabilities once again raise a question about the credibility of the current guidance and capital structure framework.”

Let’s recap – the stock is down over 50% in 6 months, they just took a $6.2 billion dollar charge against earnings, have a $2/3 billion drag on their books for the next 7 years (assuming the disaster assets of the financial arm they haven’t been able to sell don’t produce any more surprises for shareholders), they are now saddled with over $60 billion in long term net debt and can barely cover the interest expense on said debt (which is nearly $3 billion per year), again, with interest rates at/near all time lows.

Taking a 3-year average of GE’s EBIT (earnings before interest and tax) and subtracting out their interest expense they now have roughly $700 to $800 million to invest in capex (capital expenditures). It’s estimated that GE needs between $3 to 7 billion per year for Capex spending to simply maintain their respective businesses depending on which analyst you read. At what point in time do we begin to assign a negative valuation to the financial arm? The thought process being, “what they haven’t sold is what they can’t sell”? Maybe it’s so bad, there were and are no takers?

Per Marketwatch. As recently as March 4th of the 20 sell side analysts who cover GE: 5 recommended buying the shares, 12 had neutral ratings with 3 recommending selling the shares. Over 85% of the analysts have buy or hold ratings in the face of the company falling from over $30 to it’s current $13. Current Data from Nasdaq shows 3 “strong buys” 7 “holds” and 2 “sells”.

From a company I’m fairly familiar with: On April 4th, Stifel analyst Rob McCarthy discusses his outlook for GE on CNBC here, cutting his price target to $13, discussing the grim outlook for GE (excluding trade war tensions).

More from the CNBC interview:

“This is a company that could have a lot of challenges going forward in what could be a weakening underlying organic growth environment”

He notes GE’s power business has had challenges and could face more given a possible:

“Trade war, material inflation, a slower economic cycle”

When asked of his $0.86 FCF (free cash flow estimate) McCarthy describes it as, and I quote:

“A very charitable view of a company that could generate trend line cash flow from operations of about $12 billion dollars, has $3 billion dollars in capex, they’re selling several businesses, so you get to that $0.85/$0.86 number but that’s clearly a bull case from here – there is significant downside to that number in a China trade war environment or any other material down cycle environment.”

My question becomes, at what point does this stock become a sell for the majority?! Yes, there are multiple divisions of GE which are worth while, but when does the CNBC host not look at him dead in the eye and say, the stock is currently trading at $12.90 – your price target is $13.00 – and you just said X, Y & Z (all of which is negative), when should you have downgraded it to a SELL?

Is JP Morgan’s own analyst Ignorant as to how Capital Markets Function?

Dating back to a 2017 report, JPMorgan’s own analyst, Steve Tusa suggested, “trimming buyback plans” as he cut 2018’s outlook amidst restructuring due to Immelts departure. He’s also been public in stating General Electric’s turnaround plan “will require the company cut its quarterly dividend again”.

JPMorgan’s research utilizes and Overweight (OW) Neutral (N) or Underweight (UW) system so “Underweight” in the world of JPM would be a “Sell” at most other firms. They don’t directly come out and say sell, but that’s a story for a different time.

Tusa was not only in the minority with his Underweight rating, but he had been ahead of the curve, reducing his price target in the face of GE moving higher. It’s not easy to remain firm in your convictions while being on the “wrong side of the trade” for nearly a year before eventually being “proven right”.

Kudos to Tusa for his Underweight call on GE. Tusa placed himself on a virtual desert island as the majority of Wall Street analysts covering GE either held a favorable or neutral view. While “tone” of some analysts has changed, please note the Sell recommendations don’t reflect the new tone. Most analysts have dismissed the 60 plus % free fall and doubled down suggesting GE may “double” from here. And what if it does? Those who own the name higher will still be at a loss needing 135% to merely break even.

This is where Wall Street’s “Group Think” mentality becomes scary. It’s why we fall into the same traps over and over again. We will not always be right in this industry, I made a bad purchase is ok to say (so long as it wasn’t done in malice), stocks don’t always go the way we believe they will.

Discipline…

Those of you who have been with us since the beginning of 2017 may be saying, but Mitchel, didn’t the model own GE for a period of time?

The short answer is yes.

We absolutely got caught up in the “hype” of General Electric in early 2017; the quintessential turn around situation. Many divisions on their own are tremendous businesses. Their power business along with Jet Engine and medical manufacturing businesses are solid companies; they were buying back shares in droves in 2016 into early 2017 and paying that nice dividend yield. The majority of research I read was positive, there very few, sell recommendations from Wall Street research.

I had read multiple reports before buying GE, all positive but one conflicting piece of research with a contrarian view. As a contrarian myself, first instinct is to gravitate towards those pieces, though in this scenario I vividly remember a friend of mine saying, “Mitchel, it is GE” (Aaaahhh the trap). We entered the trade on 3/1/17 @ $30.15 (Blue highlight in the middle area of the chart)

As with every purchase we make, we think downside first. “If” the trade were to go against us, where would we be selling this name? Based upon past volatility and the most recent high of $33 (top left corner of the chart) we knew and understood what that number was the on the date of purchase; the only variable would be if it does close below our discipline, where would the stock trade the very next day, as that would be the day we would exit.

Our capital preservation strategy was triggered based upon the closing price on May 17th. Given our discipline, we exited the trade on 5/18/2017 @ $27.30, realizing a $2.85 a loss on a 3.77% position (Blue highlight, far right bottom corner in the above image). We were also sure to follow our (VAPS) volatility adjusted position size discipline as well.

9.45%

A handful of clients’ asked, “Why’d we sell GE, so quickly – at a loss no less?” My same friend, “but Mitchel, it is GE”. All reactions came from an emotional standpoint, no one likes to lose money on a trade. However, good investors understand a small loss is better than a large one!

I didn’t blame them for second-guessing the decision, heck; I was busy beating myself up for making the purchase. In the short term, it didn’t look as if we had made the right decision; the stock rebounded to the mid $29’s in a very few, short trading days. We acknowledge we’re not looking to be short-term traders, and this wasn’t a typical scenario for us, however, discipline is our mantra. Our goal is to allow winners to run, yet cut losers before becoming problematic.

Most of you are aware our models aren’t managed based upon an emotional approach. While we do allow for a very minimal portion of the portfolio to have a little more “rope” then the vast majority of the holdings, discipline is always paramount. Discipline trumps emotion, full stop.

While frustrated with the quick loss, what was immediately rolling through my mind was the 9.45% loss we took would require a 10.44% gain to break even on roughly 3.77% of our portfolio, a very achievable bogey.

More importantly, my thought defaults to the purpose of our discipline and model design; allow winners to run, but more so, to sell losers before becoming “problematic”!

Hindsight being 20/20, the repercussions for those who have held on to General Electric vs. where we sold it, have been fairly severe. This is the exact scenario we aim to protect against.

The first blue highlighted circle is where we bought GE the second being our sale. As I write this, GE is trading around $13.00. Had we not followed our discipline and held on we would currently be sitting with a $17.00-plus loss ($30.15 entry point – $12.80 rough current share price). This represents roughly a 60% loss.

GE will have to increase by over 136% in value to simply break even.

Without question, there will be times when this strategy will take us out of names sooner than it should, Biogen (BIIB) and Chipotle (CMG) come to mind immediately. However, over time, defending your capital against the major loses like this General Electric (GE) example will have a significantly greater, more positive impact on your portfolio. We can and do make up for moves that we may have “missed” (like that of Biogen or Chipotle), currently, we have YTD (Year to Date) moves in names like ZTO, GDS, SHOP, LNG greater than both BIIB and CMG; and many more when looking back at original purchase prices. What we don’t have are 60-plus % losses.

We bought GE as a turnaround situation, and position sized it as much. There will be other companies we invest in whose balance sheets are significantly more “bullet proof” that I’m sure we will sell based upon price action and our capital preservation strategies. We don’t get too heavily caught up in second-guessing, in our world, Discipline trumps emotion, full stop!

This time the contrarian report I had read was correct. This time, I wish I had followed the advice of the 1 vs. the many, though it doesn’t always work out this way. However, this is what makes our strategy so powerful. I will continue to beat the proverbial horse in an effort to drive this point home; how do we know when the next Lehman Brothers event comes? When the next Valeant Pharmaceuticals, Citigroup, Enron, Lucent or Bear Sterns moment will occur? The answer will always be, we don’t, and neither do the smartest on Wall Street. The majority is often wrong!

We can read hundreds of reports, the reading and research that goes into a specific buy is significant, but it’s not always right. History has proven this time and time again, this scenario is no different; how you handle these scenarios is!

I’d like to turn our attention with another scenario I believe the majority is dangerously applauding before I bring it full circle back to Mr. Dimon, Mr. Buffett and conclude…

AT&T Chief Gambled and Won Big –Randall Stephenson will reshape telecom operator into a television powerhouse…

Reads the June 12, 2018 Wall Street Journal headline, reported on by Drew FitzGerald, after Federal Judge, Richard Leon ruled in favor of AT&T’s bid for media giant Time Warner (TWX), a deal which has been pending since October of 2016.

*** It is important to note since writing this section the justice department has said it would appeal, as reported by the WSJ.

Judge Leon’s decision brought Wall Street investment bankers an early Christmas present as it appears to have opened the floodgates for a flurry of M&A activity, All eyes immediately turned to Comcast’s $65 billion dollar bid for Fox’s assets which challenged Disney’s previous offer; let the bidding war commence… ah, let’s not forget, to be financed with an absurd amount of Debt, no less (yawn). The justices department’s decision to appeal the AT&T/Time warner decision may adversely affect this bidding war?

AT&T has a current debt load of $163 billion dollars; the combined companies will carry a debt load of over $181 billion dollars on their balance sheet.

Let us ponder on this information for longer than a nanosecond. Could someone remind me again how this “gamble” is a big win?

But wait, it keeps getting better!

Don’t forget the fine print…

As reported by both the WSJ and CNBC June 13, 2018, long time AT&T analyst Craig Moffitt of MoffittNathanson recently downgraded (T) from a hold to a SELL (imagine that on, a Sell rating from a Wall Street Analyst – it’s almost as rare as spotting a white unicorn)

What’s got him spooked? The fine print…

Debt & Leverage!

“Time Warner will be a positive for AT&T’s income statement, at least initially. But it will be a negative for the balance sheet,” Moffett wrote, adding that the combined company will carry $249 billion in debt, inclusive of operating leases and postretirement obligations. “We believe that there will be continued erosion in each of AT&T’s legacy businesses as the company doubles down on bundling (discounting).”

Given the pressures in AT&T’s legacy satellite, broadband and wireless businesses and the impact to the company’s debt ratios, “AT&T will be under enormous pressure from the credit rating agencies to de-lever,” he said.

Last quarter we pondered:

“What would be worse for financial markets, Tesla filing for bankruptcy protection or AT&T’s debt being downgraded?”

We hypothesized (while providing some stark and alarming detail) as to how the structure of the corporate bond market itself could (and is likely) to be at the heart of our next credit default cycles and may be one of the largest disasters (as well as opportunities) of our lifetimes. Though, I owe readers an apology; I should have been more specific when stating the question; while most who read the note understood the downgrade we discussed of AT&T consisted of being reduced from “Bank Investment Grade” to Junk, I should have been more clear.

At the time the referenced WSJ article was written, AT&T’s (T) debt carried a Baa1 debt rating from Moody’s. More from the Journal (WSJ) article:

“Moody’s Investors Service has placed its rating of AT&T on review for downgrade pending the deal’s completion. A two-notch downgrade would put AT&T at the lowest investment grade (IG) rating Moody’s assigns, increasing the likelihood of AT&T falling into the junk-debt category.

A spokeswoman for AT&T said all major ratings firms were only considering single-notch downgrades of the company, which would leave it well above a junk rating.”

It took less than 48 hours from Judge Leon’s decision for Moody’s to cut AT&T’s debt one notch to Baa2. The Baa tranche is the lowest IG (Investment Grade) tranche on any ratings company scale – BBB (S&P and Fitch) Baa (Moody’s). However, in “part 2” of our 1st quarterly of 2018 – we noted there are 3 sub-tranches (Baa1, Baa2 and Baa3 for Moody’s and BBB+, BBB followed by BBB- for S&P and Fitch).

I want this to sink in, let me reiterate what the “spokeswoman” for AT&T said:

“All major ratings firms were only considering single-notch downgrades of the company, which would leave it well above a junk rating.”

In the IG (investment grade) world there are 8 sub tranches rated higher than AT&T’s now Baa2 rating. There is a single tranche between T’s IG rating and Junk. I am fairly certain even the least savvy of investors can figure out this spokeswoman is full of **it as T’s debt is gets closer to junk with every passing day… Based upon both, on and off balance sheet debt, it should be junk already (in my opinion).

“AT&T’s funded debt balance will exceed $180 billion following the transaction close and annual maturities will average in the $10 billion to $11 billion range. Moody’s believes that this creates a risk of diminished capital availability during times of economic stress, particularly since many fixed income investors have limited portfolio capacity to invest in additional AT&T debt and increase single issuer credit risk exposure.”

But it gets better, More from Moody’s:

The degree of any leverage improvement will depend upon AT&T’s ability to return to wireless service revenue growth while maintaining margins, and its progress stabilizing negative revenue and margin trends in its entertainment and business solutions segments.

Followed by:

AT&T’s US wireless, entertainment and business solutions segments face top line weaknesses and margin pressures amidst competitively challenging operating environments, but the strategic merger with Time Warner helps further diversify revenue sources.

From their September 7th, 2018 lows the 2 year treasury has moved from a 1.27% to a 2.60% as of July 20th , the 10 year has moved from a 2.05% to a 2.88%; these moves, over this time frame would be viewed as disasters of epic proportions had they been in the equity markets.

Moody’s states, “any leverage improvement” will depend large in part to AT&T’s ability to bring growth back to their wireless services while maintaining margins… and then proceeds to say that the wireless segment as well as the entertainment and business solutions segments face “top line weakness and margin pressures amidst competitively challenging operating environments.” Then, downgrades the combined company a single notch, after watching interest rates nearly double over an 8-month time frame?

End users are “cutting the cord” in DROVES… Personally, our “cable bill” was well north of $240 per month. After we cut the cord, between Netflix, Hulu, what we get through Amazon Prime and a few other services; we may pay $120 per-month (including high speed internet services). We “want” for nothing when it comes to television these days, pay significantly less and enjoy a much better experience with less hassle, this is what AT&T is up against on a massive scale.

All in the face of companies virtually giving products away in an effort attract new users; AT&T is currently offering a BOGO on iPhone 8’s; Verizon and Sprint have similar deals. When do you think AT&T will be returning the wireless segment to positive revenue growth? I scratch my head at Moody’s decision? Maybe the answer lies in the part of their statement, which I highlighted above?

“Moody’s believes that this creates a risk of diminished capital availability during times of economic stress, particularly since many fixed income investors have limited portfolio capacity to invest in additional AT&T debt and increase single issuer credit risk exposure.”

In plain English – too many institutional investors already own too much AT&T debt for them to buy more.

Maybe Moody’s understands that a downgrade into “junk” status might be considered capital murder for T? This is exactly the point of Part 2 of our Q1 quarterly – Please think about what would happen if all those portfolio managers who already hold too much AT&T debt had to sell into a junk market with even less buying capacity.

This is what would happen when the company is downgraded from Bank Investment Grade to Junk!

This, my friends, is what happens when too much bloody money floods a system for too long a period of time. It appears AT&T, and it’s many fixed income investors are in a bit of a pickle; and Moody’s solution is to take the hope and pray option that somehow T can grow market segments in the “face top line weaknesses and margin pressures amidst competitively challenging operating environments,” at a pace faster than that of increasing interest rates?

This is without question a gamble, but I would disagree with anyone who suggests the gamble has paid off just yet. Only time will tell on this one and while it may take a while to play out, if I were a betting man, I would take the other side of this debacle.

We’re going to finish it up and bring it back to Mr. Buffett and Dimon and the dangers of suppressing the voices of the minority

con·fab·u·late (kən-făb′yə-lāt′)intr.v.

con·fab·u·lat·ed, con·fab·u·lat·ing, con·fab·u·lates

1. To talk casually; chat.

2. Psychology To fill in gaps in one’s memory with fabrications that one believes to be facts.

In general, people don’t like to be wrong; we abhor being questioned. In the face of constructive criticism, the typical response is defensive; the critique is often taken personally.

I question thoughts or ideas of people constantly; for no other reason than, I’m curious or have an opposing view. The art of debate is gone, opposing views are construed as “fighting”. Even asking something a question as benign as, “Are you sure you’ve thought this all the way through?” turns people immediately defensive. From asking that question, I’ve literally had someone respond to me back with, “you called my idea stupid!” WHAT?

As years pass, my observation has been people get more and more defensive and less willing to admit they may be wrong. Individuals are no longer willing to admit fault or accept personal responsibility.

Admitting you’re wrong is, at times, difficult, there is nothing wrong with it – try it sometime – it’s almost as if the person you’ve apologized or admitted it to gets caught “off guard”, some even act shocked when you take accountability! Personally, I find myself to have a greater respect for those willing to take accountability; it’s refreshing.

Unfortunately, those who confabulate appear to be more prevalent then those who have the moral fortitude to admit they are wrong. As stated above, to confabulate mean “fill in gaps in their memory with fabrications that they believes to be facts.”

Society seems to be encouraging this phenomenon as we’ve become complacent and have gotten lazy. We no longer hold people accountable. If we double-check those who confabulate at all, we use a paid for fact website vs. original documents and history (reality).

We also adhere to a belief system that a title or someone’s past success guarantees them to be right all the time. It’s assumed by the masses that those individuals with “credentials” (awards, prize, titles) simply know more, and their answers or responses are always correct and those who dare to question them are wrong.

Those who do get an opportunity to ask questions, often fail to follow through with a more difficult line of questioning or call the so called “expert” out when their answers a. warrant a further, more granular line of questioning or b. the “expert” is flat out wrong.

This line of thinking is foolish. It fosters the “group think” world we live in; following the masses is applauded while disagreement is often met with venom, anger, and at times pitchforks.

What does this have to do with investing?

What if I told you that I know more about investing than Warren Buffett? You’d likely either stop reading on the spot or say, “I’m full of **it” – and to an extent, you’d be right. Yet, in merely pointing to inconsistencies with some of his recent investment choices when compared with his historical (and very public) investing philosophy, the reaction of most is virtually identical as described above; GASP, “Who are you to question Buffett”? “He’s the greatest investor of all time, what do you know?”

It’s an immediate how dare you, defensive mentality, protecting someone they have never met and likely never will.

I’ve been met with similar reactions in recent conversations I’ve had regarding my challenging of Jamie Dimon’s recent “ignorance” stance/statement relating to buybacks and dividends. What begins as a calm discussion often morphs into “you do know who Jamie Dimon is, right?!” Nah, I’ve lived in a shoe box my 22 years in the business and enjoy arguing over someone who doesn’t give a hoot about either of us, it’s fun for me; face meet palm…

Back to Buffett:

Unequivocally, Warren Buffett IS one of the greatest investors of all time. There is no argument, no debate; he’s one of the best. He’s Jordan, LeBron, Kobe, Magic, Bird, he’s top 5 in everyone’s discussion. Fight over whose #1, but he’s in that discussion.

Over the course of decades Buffett’s bedrock of investing success was built on a foundation of P&C (Property & Casualty) Insurance companies. With solid footing established, he was able to leverage the “float” created by these well run insurance companies and utilize their stable (and often) gushing cash flows to purchase large percentages, or outright purchases, of highly capital-light businesses (companies which require limited amounts of ongoing capital-expenditures (capex)).

We believe and adhere to Mr. Buffett’s philosophy and love for P&C companies as we continue to hold WRB and AFG; we’re likely to add another P&C name in the near future, too.

Though, as Mr. Buffett has aged, he’s made some tremendously questionable (some may argue poor) decisions. More importantly, breaking his personal (and becoming confabulator) in the process.

Over the last decade Berkshire’s most significant investments require significant upfront and recurring capital expenditures (capex); including Berkshire’s investments in highly regulated utilities, as well as BNSF (Burlington Northern Santa Fe, LLC); an enormous divergence from his historical norm.

At the height of the great recession, rather than buying dirt-cheap, cash gushing global dominators, Berkshire sunk $10 billion into the one time tech behemoth, IBM. Buffett had spent years suggesting tech companies were “outside his area of expertise”, one of the many reasons why he didn’t invest in them. He’s been quoted, “Never invest in a business you cannot understand.” His investment in IBM broke his own disciplines; needless to say, this investment did not end well for him.

After virtually abandoning many of his own rules (which carried him to icon status) media outlets have literally given him a free pass avoiding difficult, yet frustratingly obvious questions.

Such as: What gives?

On May 5th, 2018, 8-year-old, Daphne Kalir-Star silenced the room at the 2018 Berkshire Hathaway annual shareholder meeting, asking Buffett a simple question multi-millionaire/billionaire shareholder(s) and investors should have been asking him for years now; both for themselves as well as those whom they represent. You can watch her ask the question, followed by Buffett’s response here. Her question was met with well-deserved cheers from the packed conference crowd. Buffett and Monger responded with chair squirming, inadequate replies (my opinion).

The question from young Daphne Kalir-Star:

“Berkshire Hathaway’s best investments on which the company built its reputation has been in very capital-efficient businesses such as Coke, C’s candies, American Express and Geico. But recently, Berkshire has made really big investments in a few businesses that require huge capital investment to maintain and that offer only a regulated low rate of return such as Burlington Northern Railroad. My question to you Mr. Buffett is could you please explain why Berkshire’s largest recent investments have been departed from your old capital efficient philosophy. And why specifically have you invested (in) Burlington Northern instead of buying a capital efficient company like American Express?”

Buffett’s reply:

“You’re killing me Daphne!”

He continued:

“We’d always prefer the businesses that earn terrific returns on capital, like a C’s candy when we bought it – or a good many of the businesses and uh American Express earns a terrific return on equity and has for a very long time. Uh – the fact that we buy a BNSF (Burlington Northern) means that essentially we cant’ get more money deployed in capital light businesses at prices that makes sense to us and so we have gone into more capital intensive businesses that are good businesses but wouldn’t it be wonderful if we could run the railroad without trains and track and tunnels and bridges and a few things.”

It’s in Buffett’s response, which should make anyone who understands the definition of the word “Confabulate” to scratch his or her heads. His reply should invoke a great deal of further questioning from all shareholders… Has he just filled gaps in his memory with fabrications that he believes to be true? Companies like, Hershey, General Mills, Starbucks, McDonalds, McCormick’s or even Home Depot weren’t way cheaper (and easier for him to understand) during the 2007-2009 crises than the tech stock he admittedly had a limited understanding of in IBM?

Recently, Berkshire was willing to triple their investment in AAPL, yet couldn’t find any capital-light (as Buffett has described it) businesses cheaper than BNSF or AAPL?

For a greater understanding of what CAPEX is, listen to Buffett describe how he’d love to run a railroad without trains, tracks, bridges and tunnels. You can’t, all of the aforementioned requires an obscene amount of money to build out as well as maintain, assuming you want the company to function/operate. [These expenses are much greater than say, a chocolatier or software company with IP patents]

While I may not know more than Buffett, I do know… 1. His answer to Ms. Daphne’s question should make all investors who are paying attention, to pause and think. 2. Using capital preservation strategies (as we use) with his IBM position, would have drastically reduced his loss in that investment, improving his total performance. 3. His investments in heavy capex names like BNSF has placed a longer term drag on the overall future performance of Berkshire. Where in the past his “float” could be used to purchase highly capital efficient companies, over time, it won’t be as readily available, nor will there be as much, given the high capital expenses required to operate his utilities and BNSF. 4. The Berkshire of today is not the Berkshire that once was.

Let me be clear, Buffett’s long term track record is legendary, I am NOT being critical of this, you can see his entire history by clicking here… The man has been brilliant for decades. Though, something has changed and the change has been a drastic.

There is a quite a difference between raising legitimate questions in pointing out noticeable difference and criticizing someone’s lifetime achievements and reputation.

There is no way, given the resources and talent Berkshire has, that they weren’t able to find any cheaper, capital-light businesses to invest in, which is why they went with BNSF.

Unless….

There is one way I see these investments working out for Buffett and Berkshire shareholders. If the economy implodes, a hard recession hits and the markets nose dive, these investments could act as a recession hedge. This scenario is not out outlandish. What is outlandish was Buffett’s response to Daphne and everyone else who hangs on his every word.

Either way, if this is the case, don’t confabulate, don’t tell your shareholders you couldn’t find any capital-light businesses cheaper than BNSF; tell them you’re preparing for something bigger, tell them the truth.

In the “ignorant of how capital markets function section” I included a quote from Buffett’s 2012 letter to shareholders.

“Charlie and I favor repurchases when two conditions are met: first, a company has ample funds to take care of the operational and liquidity needs of its business; second, its stock is selling at a material discount to the company’s intrinsic business value, conservatively calculated.”

As recently as this week Buffett continues to make decisions contradictory to what he’s preached for his investing lifetime. For years Buffett preached only buying back shares at a level close to its book value. The 2012 letter to shareholders spoke of a 110% of book value. In 2016 that level jumped to 120% book value.

As of this week, Berkshire has no changed their internal policy regarding share repurchases. Rather than sticking to their 2nd rule of share repurchases, the new rule removes the 120% of book value bogey and allows Monger and Buffett to be the judge and jury of determining “below Berkshire’s intrinsic value”.

With this hurdle removed, let the financial engineering begin.

CEO’s like Buffett and Jamie Dimon have a fiduciary responsibility, an obligation to be as transparent as possible! As mentioned earlier, Jamie Dimon, suggesting those who question buybacks and dividends are ignorant to how capital markets function without further qualifying his statement is as irresponsible as it is dangerous.

Buffett and Dimon are not the only high profile confabulators of significance this quarter.

Fed Speak…

Former Federal Reserve Bank Chairman, Ben Bernanke has been doing a decent job of flying under the radar the past few years. On June 7th 2018, former Fed Chairman made news when he likened the Trump Tax stimulus to a Wile E. Coyote moment, per Bloomberg:

The stimulus “is going to hit the economy in a big way this year and next year, and then in 2020 Wile E. Coyote is going to go off the cliff,” Bernanke said

His statement piqued my interest.

Bernanke, currently of the Brookings Institute, sat down for an interview with Desmond Lachman of the AEI (American Enterprise Institute), a Washington “think tank”. Rather than fast-forwarding find context to his Road Runner reference, I decided to watch the entire interview. After watching and listening to the interview countless times as I transcribed his words to paper, I still, to this moment, continue to struggle with many of Mr. Bernanke’s responses. I am also finding difficulty in understanding why the media has focused on the part of the discussion they have?!

Confabulate is a constant theme for the quarter. For the life of me, I can’t figure out if Bernanke and his ilk (Dimon, Buffett, Yellen (as you’ll see below)) convince themselves that what they are saying is factual? Are they blinded by arrogance? I don’t know if they become obsessed with their power or are too rigid in the belief of their academic models (which often don’t translate well into real life)?

My leading theory remains; they are all just terrified of the likely outcome, should they be the one who tell the truth, which sets the house of matchsticks ablaze.

Highlighted below, please find some of the more head scratching moments from the interview. We attempt to quote Mr. Bernanke verbatim, though he mumbles at times. This is a 40-minute-plus interview, which is extremely difficult to quote and paraphrase, so I invite you to watch the interview in its entirety for full context.

The discussion began with Bernanke telling the audience the QE programs were necessary and all Fed officials were onboard and believed QE was, “the best option we had”

“We (the FOMC) didn’t know where the bottom was going to be and we were seriously concerned we were facing a new depression type situation – The staff was telling us that we needed 400 basis points more of stimulus, we had zero to give… because interest rates had been at zero since the previous November. So we needed to do something, and all members of the FOMC from the most dovish to the most hawkish were very strongly agreed with this was the best option we had.”

Danielle DiMartino Booth is a former advisor to Dallas Fed president Richard Fisher. She’s also the author of ~Fed Up – An insiders take on why the Federal Reserve is Bad for America, this should be required reading for all investors. It is an incredibly detailed account of what goes on inside the walls of the Federal Reserve Banking system, more specifically; she details her personal experience at the Dallas Fed before, during and after the great recession of 2007-2009.

Bernanke tells Lachman QE was the best option at the time agreed upon by the most dovish to hawkish fed presidents, yet DiMartio Booth, both in the book as well as publically speaks of a facility that she and Dallas Fed President Fisher created to resolve the freeze up in the commercial paper market rather than opening Pandora’s box with QE.

“The liquidity measures that were put in place to unfreeze the credit markets by the NY Fed had squat (that’s a technical term) diddely squat to do with the Fed expanding its balance sheet. One did not have to go along side the other – it was a liquidity freeze that needed solving not the QE 2 and QE 3 that again, just benefited a few.”

“Again, I was there at the time when then Dallas fed president Richard fisher asked me to get all the top ranked commercial paper on planet earth and we created a facility at the time live on the ground to resolve the freeze up in the commercial paper market.”

~Danielle, DiMartino Booth; Stansberry Investor Hour Podcast #17 September 14, 2017

While I tend to believe DiMartino Booth, without significant digging, this can be chalked up to conjecture. What really starts to bother me is when Bernanke begins to speak to the cost/benefit analysis the Fed took into consideration with the QE program, suggesting the majority of studies show the QE programs to have been “effective”:

“The great majority of studies suggest that this was effective, that it did ease financial conditions, it did provide support for the economy.”

“I think on the benefit side it was positive it contributed to the recovery and gave us a tool where out traditional short rate mechanism was no longer available.”

When speaking of cost however, he becomes, dismissive and smug, speaking almost with an “I told you so, smirk” on his face.

“A lot of this discussion is going to be about the costs. We approached this very carefully because we were concerned about the costs…

…let me just say that (uh) many of the costs that were anticipated by outsiders simply have not happened. When we did the second round of quantitative easing (QE) in November of 2010 we got a letter from congress followed up by a letter from a number of hedge fund managers and economists imploring us not to do this terrible thing and among the things they were concerned about was the possibility of hyperinflation – very high inflation; a collapse of the dollar or as they put it “debasing the currency”, and of course, none of those things have happened, and indeed, markets have functioned well…

…while we certainly have not existed yet, the exit process has begun, asset purchases ended in October of 2014; now we’re at a process of where the balance sheet is actually beginning to run off and of course, it hasn’t finished, but that also has not shown itself to be a big problem so far”

How Bernanke defines QE’s effectiveness is where my ire originates. While he does point to metrics like unemployment and inflation as QE’s proof of success, he brushes over Lachman’s concern of Global Asset Price Inflation, then returns to his primary “go to” cost vs. benefit barometer of none other than Equity Markets?

“Let me just give you a few examples in 2010 this letter I mention from the congress they talked about asset bubbles as being a major concern at that time the Dow jones was less than 12,000 now it’s 25,000 I think a lot of that gain is not bubble I think a lot of it reflects genuine economic growth and also low interest rates and taking those two things into account its not obvious that stocks are wildly overvalued, they’re a little bit overvalued but not wildly.”

More…

So yes, it’s possible that at some point their will be a problem, but again the Fed is looking at this very carefully, monitoring it and secondly, we’ve seen tremendous benefits for the economy; so I’m not that concerned about it I think that actual assessments of for example the stock markets suggests its not wildly over valued, in any case you know it seems as though most of the gains is related to the progress most of the economy has made.”

When speaking to the cost/benefit analysis, his cost references are constantly to equity markets; “the stock market suggests it’s not wildly overvalued”?!

Let that sink in… please… Neither he, nor any Fed official or PhD working at the Federal Reserve, have seen any stock market bubble in modern history. Greenspan’s “irrational exuberance” speech came 3 years before the tech bubble collapse, and it’s not like he was banging a gong for the 3 years leading up to the eventual crash.

Yellen has flatly admitted (as you’ll see below) she saw none of the housing crisis coming; yet, Bernanke is constantly pointing to the equity markets as a measure of QE’s effectiveness, as well as a measurement of value?

Bernanke’s continues to suggest the benefits of QE have outweighed the costs, but he refuses to speak of the costs. What he speaks of during the interview are the “expected costs” that “haven’t happened yet” (i.e. High inflation (hyperinflation) or debasing of the currency).

He conveniently avoids addressing any costs (foreseen or unforeseen) so I’ll give you one…

“By mid-2016, long-term returns for U.S. public pensions have dropped to the lowest levels ever recorded – a $1.25 trillion funding gap – forcing pension fund managers from New York to California to resort to even riskier investments to meet their legal obligations – and to cut services to make up the shortfall”

Buried in a last minute amendment of the December 2014, $1.1 Trillion-dollar spending bill, more than 1-million retired union employees watched their pensions get reduced to rubble when the House and Senate approved a plan to allow pension fund managers to cut their once, legally obligated retirement benefits to those retirees who paid into a system over the course of their working years.

With the stroke of a pen, the promise of a un-interrupted, guaranteed lifetime income stream has been taken away from hundreds of thousands to possibly millions of retirees; those who can’t go back to work.